Merged mining refers to the process of reusing (partial) PoW solutions from a parent cryptocurrency as valid proofs-of-work for one or more child cryptocurrencies.

(This post is also avalable on Medium)

Merged mining was introduced as a solution to the fragmentation of mining power among competing cryptocurrencies and as a bootstrapping mechanism for small networks. Merged mining was first implemented in Namecoin in 2011, with Bitcoin acting as the parent cryptocurrency. One of the earliest descriptions of the mechanism as it is used today was presented by Satoshi Nakamoto in a bitcointalk forum post. Apart from the source code of the respective cryptocurrencies implementing merged mining, a technical explanation is given in the Bitcoin Wiki.

For a parent cryptocurrency to allow merged mining it must fulfill only one requirement: it must be possible to include arbitrary data (usually the output of a cryptographically secure hash function) within the input over which the proof-of-work in the parent is established. The main protocol logic of merged mining in turn resides in:

-

The specification and preparation of the data linked to (or included in) the block header of the parent, e.g., a hash of the child block header.

-

The implementation of the verification logic in the client of the child blockchain, i.e., the child blockchain must be able to verify the PoW of the merge-mined blocks accepted from the parent chain(s).

Miners participating in merged mining are required to run a full node for the respective child cryptocurrency (Miners can decide to perform so called SPV mining, i.e., not verify transactions included in blocks, or simply ignore transactions at all. This, however, can be considered malicious behavior as it may damage the child blockchain). Analogous to the normal mining process, unconfirmed transactions are assembled into blocks for both the parent and any merge-mined cryptocurrencies selected. The hash-based proof-of-work of the herein considered parent cryptocurrencies has the property that any modifications to the input, namely the block header and subsequently the entire data of the block, would invalidate the PoW with high probability. Therefore, including data, such as a hash of the to be mined child block header, anywhere in the parent block implicitly links the child block to the parent block’s proof-of-work.

Miners then proceed to follow the normal mining process, looking for valid solutions to the parent’s PoW puzzle. Each time a solution candidate is found, miners can perform the following actions:

-

In case the PoW solution of the parent block meets the difficulty requirements of the parent cryptocurrency, miners create a regular parent block following the normal mining procedure.

-

Independent thereof, if the PoW solution of the parent block meets the difficulty requirements of any of the child blockchains, the respective child block is considered valid and can be published in that child’s network.

To ensure nodes in the child blockchains are able to verify the correctness of a merge-mined child block, miners must include all data relevant for validating the proof-of-work of the parent blockchain, as well as the data linking the child to the parent’s PoW.

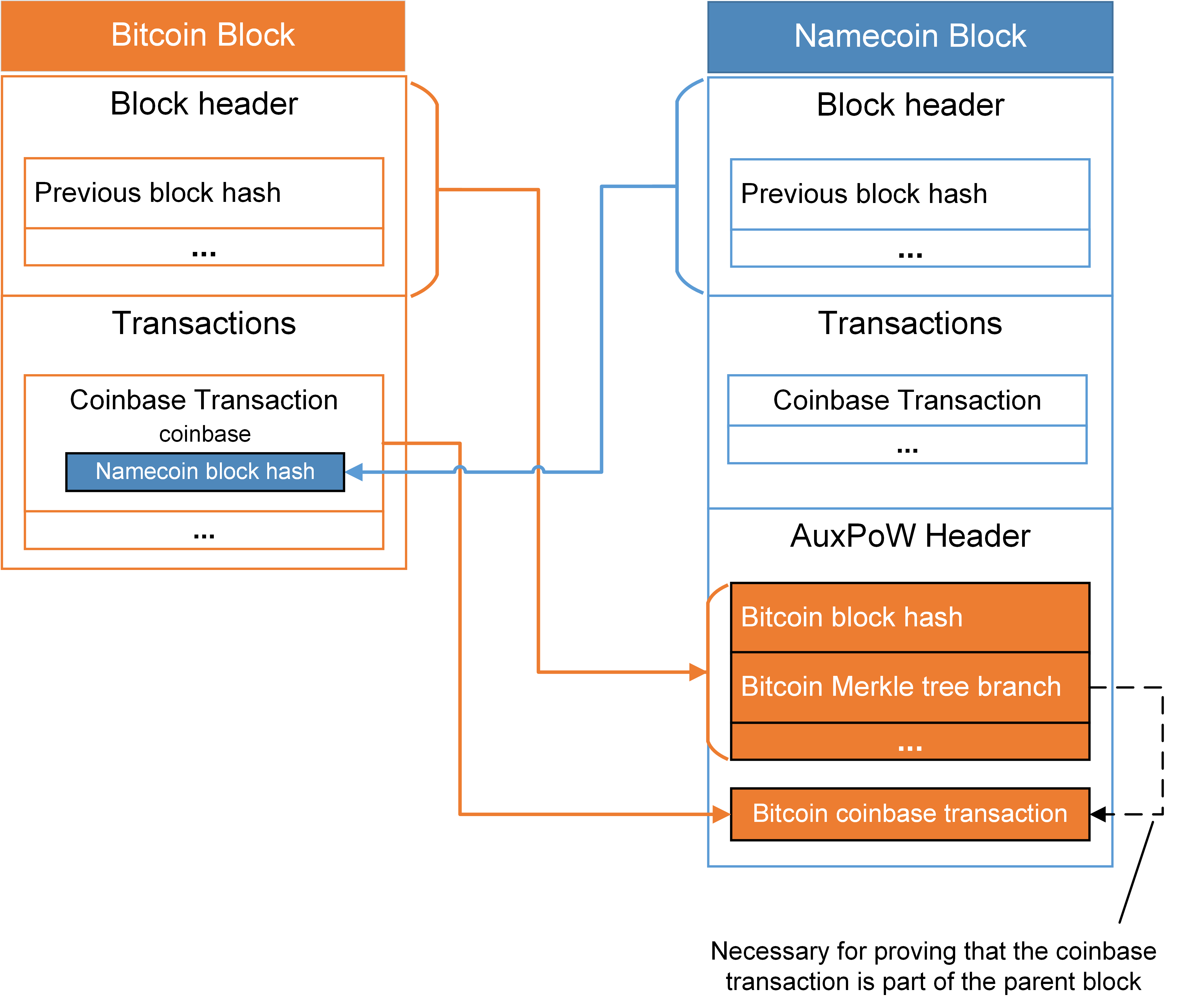

Structure of merged mined blocks in Namecoin. The block hash of the to-be-mined Namecoin block is included in the coinbase field of the Bitcoin block. Once a fitting PoW solution is found, information from the Bitcoin block header and the coinbase transaction are included in the Namecoin block. Note: the Bitcoin Merkle tree branch is necessary to verify that the included coinbase transaction was part of the respective Bitcoin block.

Structure of merged mined blocks in Namecoin. The block hash of the to-be-mined Namecoin block is included in the coinbase field of the Bitcoin block. Once a fitting PoW solution is found, information from the Bitcoin block header and the coinbase transaction are included in the Namecoin block. Note: the Bitcoin Merkle tree branch is necessary to verify that the included coinbase transaction was part of the respective Bitcoin block.

In Namecoin, for example, the parent block header and coinbase transaction are included as additional, so called AuxPoW, header in merge-mined Namecoin blocks. The coinbase transaction is the first transaction in a block and is used to distribute newly generated coins to miners. It also allows to store up to 96 bytes of arbitrary data in the so called coinbase field. During the process of merged mining Namecoin with Bitcoin, miners reference the hashes of the to-be-mined Namecoin blocks in the coinbase fields of the to-be-mined Bitcoin blocks, linking the Namecoin blocks to Bitcoin’s PoW. As a result, nodes in the peer-to-peer network of Namecoin can verify that the PoW for the submitted blocks was correctly performed as part of the mining process of the parent cryptocurrency, namely Bitcoin.

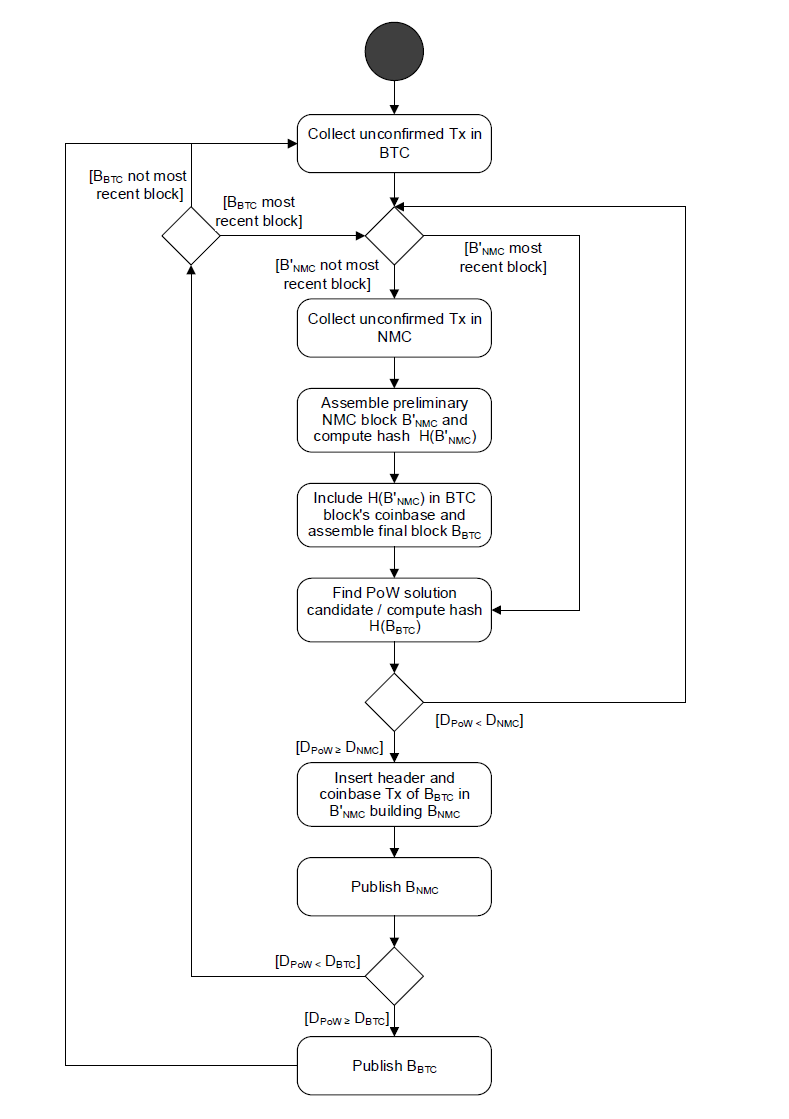

The process of merged mining on the example of Bitcoin and Namecoin is shown in the following Figure:

Process of merged mining as performed by miners when merged mining Namecoin with Bitcoin. Note: for simplification and based on real-world observations we assume the PoW difficulty required by Bitcoin is higher than the PoW difficulty required by Namecoin.

Process of merged mining as performed by miners when merged mining Namecoin with Bitcoin. Note: for simplification and based on real-world observations we assume the PoW difficulty required by Bitcoin is higher than the PoW difficulty required by Namecoin.

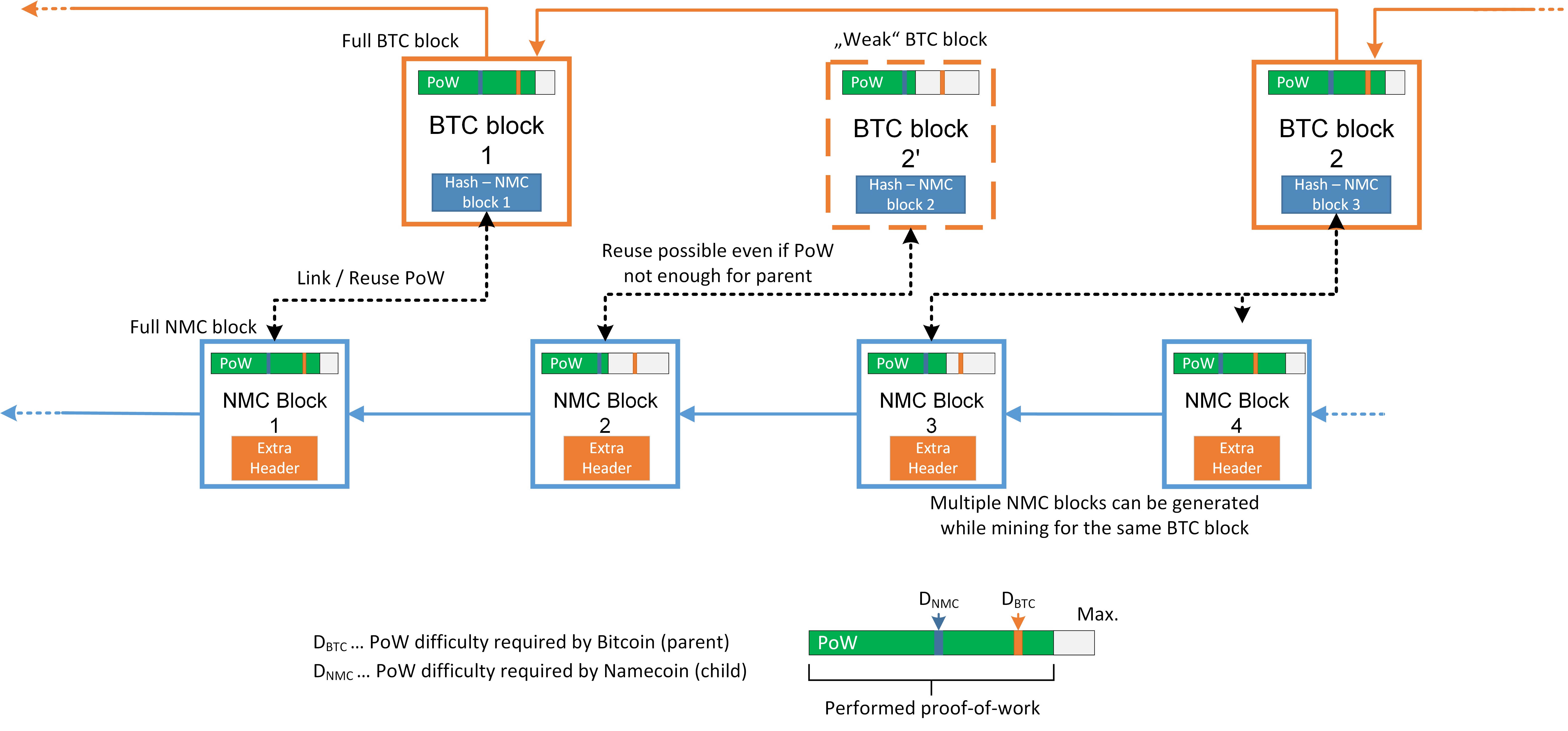

When merged mining, each parent block can be responsible for the generation of multiple child blocks, i.e., miners may find multiple PoW solution candidates below the difficulty of the parent but meeting the requirements of the child blockchain. Furthermore, even if a block mined for the parent chain does not satisfy the difficulty requirements of the parent, it can be used for generation of blocks in the child, given that the respective child difficulty is met.

Overview of merged mining in Bitcoin with Namecoin. Assuming lower PoW difficulty requirements, Blocks accepted in Bitcoin will be accepted in Namecoin. However, even blocks missing the difficulty target for Bitcoin, can still meet the requirements for Namecoin, as shown for BTC Block 2’. Furthermore, as depicted for NMC Block 3 and 4, a single BTC block can be referenced my multiple NMC blocks, if numerous solutions meeting NMC’s difficulty are found in the process of mining.

Overview of merged mining in Bitcoin with Namecoin. Assuming lower PoW difficulty requirements, Blocks accepted in Bitcoin will be accepted in Namecoin. However, even blocks missing the difficulty target for Bitcoin, can still meet the requirements for Namecoin, as shown for BTC Block 2’. Furthermore, as depicted for NMC Block 3 and 4, a single BTC block can be referenced my multiple NMC blocks, if numerous solutions meeting NMC’s difficulty are found in the process of mining.

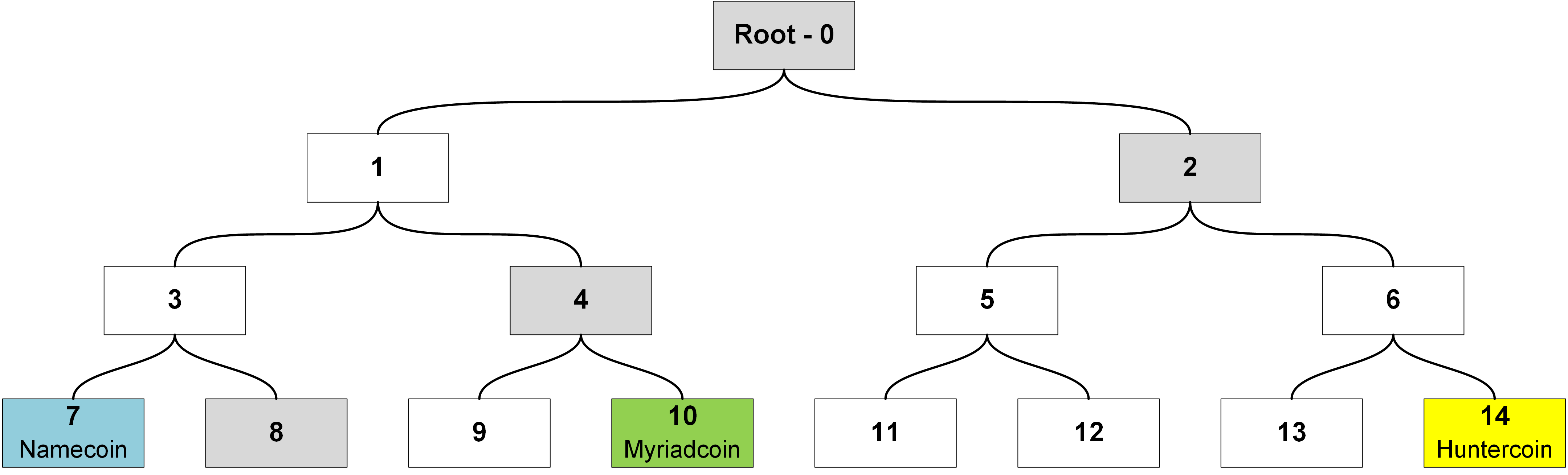

As mentioned, a single parent can be used to perform merged mining on multiple child chains. This can be achieved by including the Merkle-tree root of a Merkle tree, containing the block hashes of the child blocks as leaves, in the coinbase field of the parent block. In addition, the size of the Merkle tree and the path to the position of the respective block hash must be provided. An exemplary visualization of the used Merkle tree structure is given in the Figure below.

Visualization of a Merkle tree used when merge-mining multiple child cryptocurrencies in parallel. For Namecoin to be able to verify that the respective block hash is contained in the Merkle tree at position 7, hashes of the fields 8, 4 and 2 (colored in grey) must be provided in addition to the root hash (0). Furthermore, the order in which to apply the given hashes (in our case “right”, “right”, “right”) must be included.

Visualization of a Merkle tree used when merge-mining multiple child cryptocurrencies in parallel. For Namecoin to be able to verify that the respective block hash is contained in the Merkle tree at position 7, hashes of the fields 8, 4 and 2 (colored in grey) must be provided in addition to the root hash (0). Furthermore, the order in which to apply the given hashes (in our case “right”, “right”, “right”) must be included.

Thereby it is necessary to make sure that a miner cannot mine on different branches of the same child blockchain, as this conflicts with the rules of the underlying Nakamoto consensus mechanism and would make double spending attacks possible. Hence, each cryptocurrency must specify a unique ID, which can be used to derive the leaf of the Merkle tree where the respective block hash must be located.

The aim of the introduction of merged mining was, on one hand, to disincentive miners of large and established cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin to switch their mining activities to emerging cryptocurrencies. As such, these miners were given the possibility to continue mining on the established cryptocurrencies, while also generating profits in merge-mined child blockchains. For small and newly created cryptocurrencies, which have not been able to accumulate a sufficiently large number of miners, merged mining provides access to the large computational capacities of established blockchains like Bitcoin. Thereby, the motivation for small cryptocurrencies is to make attacks on the network more costly, hence improving the security of the underlying system (In theory, miners of the small cryptocurrencies switching to merged mining move their computational resources to the parent, this way to some extent increasing the overall mining power of the parent).

By implementing merged mining, child cryptocurrencies permanently bind themselves to the parent(s), becoming reliant on the respective mining community. On one hand, it becomes very difficulty for child cryptocurrencies to switch back to normal mining, without facing the threat of significant hash rate loss. In fact, to this date we are not aware of any successful attempts. On the other hand, concerns with regards to potential risks of mining power centralization have been voiced in the community, although no study has yet been conducted to verify these claims. Ideally, the permanent parent-child relation triggers no significant negative effects, apart from the child being dependent of the parent’s community and developments. However, as we show in the rest of this thesis, this is not the case in reality.

Related Work

Previous research related to merged mining is mostly focuses on the application layer of the underlying cryptocurrencies. A short description of merged mining is provided by Kalodner et al. in an empirical study of name squatting in Namecoin. Ali et al. highlight that Namecoin suffers from centralization issues linked to merged mining, but do not provide details on the extent of the problem. Other descriptions of and references to merged mining can be found in:

-

L. Anderson, R. Holz, A. Ponomarev, P. Rimba, and I. Weber. “New kids on the Block: An Analysis of Modern Blockchains”. PDF

-

https://github.com/namecoin/wiki/blob/master/Merged-Mining.mediawiki#Goal_of_this_%20namecoin_change

-

A. Narayanan, J. Bonneau, E. Felten, A. Miller, and S. Goldfeder. “Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: A Comprehensive Introduction”. Princeton University Press, 2016

-

Rootstock Whitepaper. PDF

-

A. Back, M. Corallo, L. Dashjr, M. Friedenbach, G. Maxwell, A. Miller, A. Poelstra, J. Timón, and P. Wuille. “Enabling Blockchain Innovations with Pegged Sidechains”. PDF

A detailed analysis of the effects and implications of merged mining on the security of the implementing cryptocurrencies, showing merged mining increases centralization issues in child cryptocurrencies, is provided in the paper “Merged Mining: Curse or Cure?”.

(Disclaimer: The text in this article is an edited excerpt from my Thesis: “*Merged Mining: Analysis and Implications”, A. Zamyatin, MSc Thesis, TU Wien, 2017, *PDF available here)